What is the fastest way to sail across the Atlantic? (Part 2)

Two weeks ago, Kevin told us all these exciting stories about explorers like Columbus and Vespucci who only crossed the ocean with the help of the wind in their sails. I couldn’t stop thinking about those trade winds – the special winds that helped sailors get from Europe to the Americas long ago. So I asked Kevin again, and now I understand how they actually work.

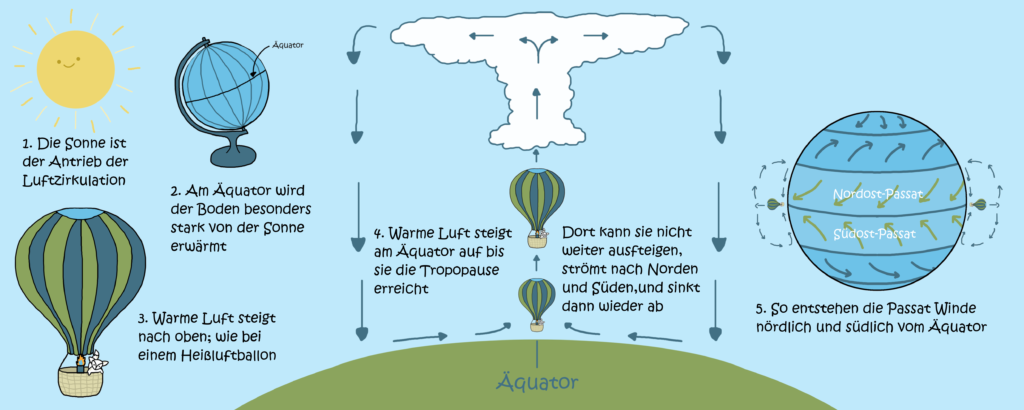

It all starts around the equator, the warm part of our planet that divides the earth into northern and southern hemispheres. At the equator, the sun can heat the ground particularly strongly. This causes the heated air to rise like a hot air balloon. The water from the ground also evaporates and rises. As the air rises higher, it expands and becomes colder.

This means that as the balloon expands, it gets colder and colder inside, and at some point, it becomes so cold that the water vapour in the air starts to condense, forming clouds. At some point, the balloon reaches a height at which it can no longer continue to rise. This height is known as the tropopause.

From there, the air spreads out sideways and flows north and south, cooling and beginning to sink downwards. As the air sinks, it warms up again (just as an air pump warms up when you inflate a bicycle tire!). Once at the bottom, the air then flows back towards the equator. However, instead of flowing straight back to the equator, it is deflected slightly to the west due to the Earth’s rotation. So the air flows back along the ground from east to west, forming the trade winds that were so useful to ancient sailors. The trade winds are part of a huge loop called the “Hadley cell” after its discoverer George Hadley.

Lass dir den Beitrag vorlesen

Text: Kevin Wolf, Illustration: Patrizia Schoch